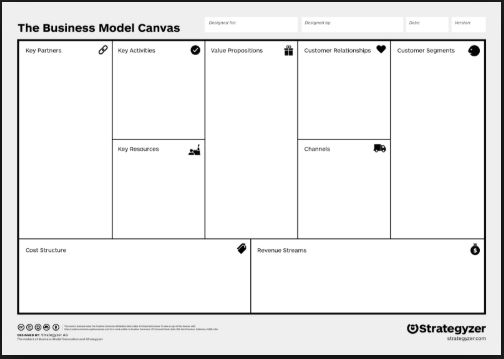

The publication in 2010 of Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur’s Business Model Generation has proven highly influential in both the theory and practice of management consulting. The book’s lasting gift to this world has been the Business Model Canvas (BMC), a cartographical representation of nine elements of a business model.

The widespread adoption of the BMC as a tool for identifying and exploring the connections between various elements of business models is not just due to Osterwalder & Pigneur’s decision to publish this work under creative commons. It also defines the often ambiguous term “business model” through the articulation of its component parts, allowing an easily accessible starting point for definitional debate. It also illustrates its own definition neatly on one page, in a layout which, taking its lead from design thinking principles and left brain/right brain interaction, prompts engagement and connection spotting from those working with it.

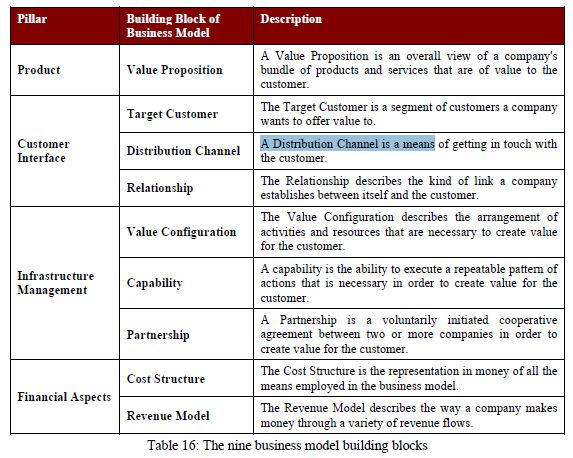

The BMC is not an insubstantial thought bubble from the latest management theorist du jour. The research upon which it is based comes from Osterwalder’s doctoral thesis of 2004, The Business Model Ontology: A proposition in a design science approach. Osterwalder describes business model ontology as “a set of elements and their relationships that aim at describing the money earning logic of a firm” (Osterwalder 2004). From here, he dissects existing approaches to describing models and comes up with his own framework, which he then tests on a creative industries business (the Montreux Jazz Festival). In his description of the building blocks of a business model, we can see the nine elements which eventually found their place on the BMC.

Since 2010, I have often used the BMC as a consulting tool in my work with businesses and not-for-profit organisations. My approach to using the canvas is, I suspect, a common one. Participants are presented with a large scale printout of the canvas (A0 size), and through a structured conversation, I invite them to fill in the elements of the canvas in sequence, starting with the value proposition and the customer segments, two closely related components.

Participants are asked to describe what makes up each element and their responses are written on post-it notes, which are stuck on the canvas in the appropriate square. Although the workshop follows a methodical “one square at a time” approach, participants are able to apply post-it notes to any square at any time, in a way which doesn’t restrict participation to a strictly linear thought process. The result of a successful BMC session is a fully notated canvas, which serves as a map of a company’s business model, through which its strengths, weaknesses and opportunities become apparent.

The BMC is not without its limitations. It has no obvious placement for consideration of market forces and/or competition, which may influence the development of a business model. In addition, there’s no prescribed method for what to do with a completed canvas – participants must formulate their own next steps. As a tool, it is illustrative rather than diagnostic. However, I have found it useful when helping someone test a potential business idea and to inform a decision to proceed or retreat from it.

Numerous adaptations of the canvas have sprung up, taking advantage of its status as a work published under creative commons. Although many of these stray from Osterwalder’s original principles of describing a business model, they can at times provide more practical tools for entrepreneurial planners. The Lean Canvas by Canvaniser, for instance, replaces the slightly pedestrian “infrastructure management” elements which Osterwalder favours, with a trendier “problem/solution” match. Other adaptors have nudged the BMC canvas away from business modelling, to mapping value in other spheres. Emma Williams has proposed a Research Canvas for sketching out the elements of a research problem. Many more are easily found online, but the best adaptations are based on a sound understanding of Osterwalder & Pigneur’s original work and also mimic its careful approach to design. So canvasses have become a distinct genre within consulting methods (interestingly, as a concept, it predates the BMC. Osterwalder’s original thesis references Kim and Mauborgne’s “strategy canvas”, in an early indication of where his ideas were heading).

There are three aspects of this ongoing reimagining of the business model canvas which I’m thinking about, as I work towards formulating a method for my own research.

The first is the adoption of what we might call “canvassing” – the creation of a notated canvas in a workshop format, conducted a facilitated conversation – as a useful method for data collection. This is a technique which seems to have emerged from mind mapping and process mapping, to become something distinct among consulting methods, of value to both participants and facilitators. It seems there is something about facing a large scale map of an idea and physically interacting with it, which promotes a level of engagement with the topic and aids an analytical consideration of an idea’s component parts. It is possible, I suggest, that as a qualitative research method, canvassing would be a useful alternative to interviews.

The second is that the constant revision of the canvas into new forms establishes a precedent of adaptation, and offers the possibility of examining the journey of creative industry entrepreneurs in a similar way. A non-linear graphical approach may also suit the subjects, as it may aid those exhibiting entrepreneurial cognition (or creative cognition, as I imagined it here) and support their ability to spot linkages between seemingly disparate elements.

As discussed previously, entrepreneurship can be seen as a process and that process can be mapped in a way which demonstrates how entrepreneurs and their ventures develop. That entrepreneurial journey can, I suggest, be converted into a BMC-style canvas and used as a research tool for collecting data from creative industry entrepreneurs, in a workshop format.

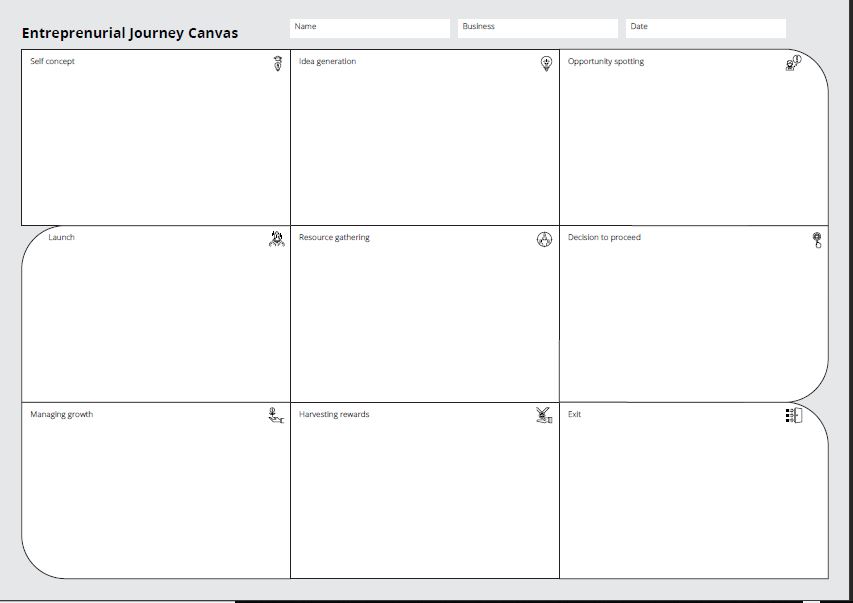

A first version of an Entrepreneurial Journey Canvas (EJC) is presented here. It retains the linear progression of the entrepreneurial journey, as informed by Baron & Shane, but adopts a simplified BMC-style layout which hopefully prompts cognitive leaps between its various elements. Much like with a BMC session, the end result of the workshop would be a notated canvas of an entrepreneurs’ journey, from which key themes could be identified and easily coded.

The table below shows the nine elements of EJC: six process stages and three decision points. It also shows suggested questions which may be asked in a facilitated workshop format to elicit insight from participants.

| Element | Type of Element | Suggested questions |

| Self-concept | Process | How did you imagine yourself to be an entrepreneur?

What role models did you have? What made you think you could do it? What did you imagine the rewards to be? |

| Idea Generation | Process | What sparked your idea?

What interests led you to it? What dots did you connect to get to that idea? |

| Opportunity spotting | Process | What was the market opportunity you saw?

How did you identify it? What helped you decide it was the right time to pursue the opportunity? |

| Decision to proceed | Decision point | What made you finally decide to press go?

What did you need to stop or give up to proceed? |

| Resource gathering | Process | What resources did you need?

How did you procure them? What barriers did you face? |

| Launch | Decision point | What did it take to get here?

What happened immediately before and after launch? |

| Managing growth | Process | How did you grow/develop the venture?

What were the big moments? What went well and what didn’t? |

| Harvesting rewards | Process | Were the rewards monetary or other?

Were they what you expected? Were you satisfied with them? Was it all worth it? |

| Exit | Decision point | How did you decide to exit?

Was it forced on you or was it entirely your choice? What is the legacy of your entrepreneurial venture? |

Feedback on this embryonic version of the EJC and its potential as a research tool is welcome, via the comments section. Does it have potential as a method for collecting data on the journeys of creative industries entrepreneurs? What problems do you foresee? What changes would you make to it? What is unclear about it? And is “canvassing” a viable research method to employ?

Download version 1 of the EJC.

With thanks to Wendy Mather, for valuable comments on the entrepreneurial process, non-linear thinking and for “gussying up” Version 1.